1 Disgraced Civil War General + 1 Ardent Atheist = Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ

Chariot race, Ben Hur

During our first year of marriage, my husband Rob and I rented the classic film Ben Hur with Charlton Heston to watch the night before Easter. The chariot race came up awfully fast. "I feel like we're supposed to care about who wins," I told Rob. "Shouldn't we get to know the characters a bit?" The movie was over in less than an hour. "Huh. I thought this was supposed to be a long movie." We shrugged and shook our heads. Only after taking the disc out and examining it more carefully did we realize what happened. We had played Side B.

Tonight my family and I are watching Ben Hur starting with Side A. (Funny how it's so much more satisfying that way.) It's a night-before-Easter tradition we cherish every year. The hope and awe of the characters when Christ is raised from the dead is absolutely contagious. and the best part is knowing that that Christ, the one who healed lepers and mended broken lives, is still alive, and He is my Christ, my Lord too. Hallelujah! A couple of years ago, while I was writing my Civil War series, I was delighted to learn that Lew Wallace, the author of Ben Hur, was a Civil War general before writing the novel. But it was only a few days ago that I learned more about the amazing story of how it all came about.

[[{"type":"media", "view_mode":"media_large", "fid":"1192", "attributes":{"class":"media-image wp-image-2924", "typeof":"foaf:Image", "style":"", "width":"500", "height":"672", "alt":"Lew Wallace, circa 1861"}}]] Lew Wallace, circa 1861

In September 1876, Wallace was on his way by rail to join thousands of other Union veterans at the Third National Soldiers Reunion in Indianapolis. When a man Wallace recognized popped into his sleeper car and invited him to have a talk, he agreed. The man was Robert Ingersoll, who had been a soldier at the Battle of Shiloh, where Wallace's military reputation had been stained by not bringing his men to the battle in time. In fact, the Union defeat at Shiloh was blamed, at least in part, on Wallace's failure. But Ingersoll, now the nation's most prominent atheist, didn't want to rehash Shiloh with the general that night on the train. Instead, he wanted to share his passion: the nonexistence of God.

Ingersoll talked until the train reached its destination. “He went over the whole question of the Bible, of the immortality of the soul, of the divinity of God, and of heaven and hell,” Wallace later recalled. “He vomited forth ideas and arguments like an intellectual volcano.” The arguments had a powerful effect on Wallace. Departing the train, he walked the pre-dawn streets of Indianapolis alone. In the past he had been indifferent to religion, but after his talk with Ingersoll his ignorance struck him as problematic, “a spot of deeper darkness in the darkness.” He resolved to devote himself to a study of theology, “if only for the gratification there might be in having convictions of one kind or another.”¹

Rather than study a stack of theology books, however, Wallace took a completely novel approach--literally. He decided to explore the divinity of Christ by writing a novel about Him. That novel was born four years later in the form of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, and was to become one of the best-selling American novels of all time. What delicious irony! A late-night conversation in which an atheist tried to persuade another into the camp of unbelief actually set the wheels in motion for one of the most influential biblical epics ever written. Amazing. Literature critics were less impressed, but readers loved it. The book sold as many as a million copies in its first three decades in print.

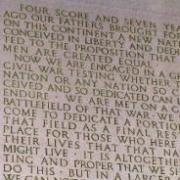

Ulysses S. Grant read Ben-Hur in a single, 30-hour sitting. President James A. Garfield wrote to Wallace after finishing it, "With this beautiful and reverent book you have lightened the burden of my daily life.” Jefferson Davis's daughter Varina read the novel to him from night til dawn, "oblivious to the flight of time."² Ben-Hur was published fifteen years after the end of the Civil War, and a few years after the official end of the Reconstruction Era. It is the story of compassion triumphing over revenge, and of Christ's resurrection. I can only imagine how that must have resonated with Americans struggling for rebirth. [Tweet "Because Jesus lives, Hope lives."] The truth is timeless, for those who saw the risen Christ, for Americans piecing their lives back together after the Civil War, for you and for me. Because Jesus lives, Hope lives.

Happy Easter, friends! He is risen!

Sources: 1. Swansburg, John. "The Passion of Lew Wallace," Slate.com. March 26, 2013. 2. Ibid.